Unama’ki visit

Written by the Sámi regional team

The Sápmi research team visits fellows in Unama'ki—“The land of the fog”, Canada.

In August 2025, the Sámi Sharing Our Knowledge regional project–team visited the Bras d’ Or Lakes region in Unama’ki, to get to know Mi’kmaw culture and the context of climate risks to lands and watersheds. See the map of the journey in this StoryMap. The purpose of travelling was to build relationships by getting to know each other's cultures, exchanging experiences, and mutual learning regarding challenges related to managing water and rivers. This is particularly relevant for understanding the context of climate change and Indigenous solutions to these complex problems.

Flying over Unama'ki. Photo by Kia Krarup Hansen

This was the third in-person meeting between the Sámi and the Mi'kmaq during the Sharing Our Knowledge project, after vists from Unama'ki to Sápmi in October 2024 and June 2025. The first meeting took place during the 2nd International Indigenous Salmon Peoples Gathering in international Indigenous salmon gathering in Kárášjohka/Karasjok, Sápmi. The second meeting was the “River Dialogues Across Sápmi” tour (see blog), which was organized as a research field visit and symposium in collaboration with other research groups. On the previous meetings Mi’kmaq people and participants from Dalhousie and Cranfield Universities came to Sápmi to learn about Sámi culture, focusing on the Tana River system and river Sámi culture. The Sámi team consisted of ten people from UiT The Arctic University of Norway, the Sámi Parliament, the Joddu – the wild salmon centre in Tana and Sámi artist and illustrator Kine Kjær. The delegation also included a couple of young "salmon ambassadors" from the Deatnu – Tana river valley, supported by the Sámi Parliament.

Team meeting at Dalhousie University, Halifax. Photo by n.n.

(Left to right (front row): Graham Gagnon, Kine Yvonne Kjær, Camilla Brattland, Camilla Mudenia, Madison Gouthro, Lorraine Marshall, Elisabeth Erke, Sherida Hassanali, Andrea Momblanch, Megan Fuller, Hege Persen, Shelley Denny, Elder Ann LaBillois, Kia Krarup Hansen, John R. Sylliboy; (back row): Jon-Christer Mudenia, Tommy Ose, Harald Persen, Alitta Sylliboy Patles, Emalie Hayes, Bob Grabowski, Theresa Afi, Heather Smith, and Vegar Bæhr

Arriving in Mi’kma’ki The home of the Mi’kmaw

Unama'ki means “Land of the fog” and is the unceded and traditional territories of the Mi’kmaq people located, in what is now known as Nova Scotia, on the east coast of Canada. In Unama'ki several Indigenous communities are gathered around the Bras d’Or Lakes (see map), which is a large water system with connected salmon rivers and waterways.

Bras d`Or region. Photo by Kia Krarup Hansen

Sámi Parliament Councillor Elisabeth Erke, from Polmak in the Deatnu river valley, participated as the Sámi Parliament's representative. Elisabeth was interviewed for the newspaper Ságat after her arrival back to Sápmi. In the interview, she tells that throughout her life, people have looked up to Canada when it comes to indigenous issues, First Nations and all that this entails. She immediately felt at home in Unama’ki: «Finally getting to Canada was great. I felt at home there, a sisterhood, simply put. »

With wonderful hospitality the Canadian and Mi’kmaq hosts had organized a well-planned programme packed with activities for our trip to Canada. The participants were given tours of museums, a water research institute, a fish hatchery, took part in spear fishing, and a walk through the historic area of Goat Island, with an introduction to history, culture, building traditions, rituals, practices, and history on many levels. The various activities aimed at exchanging culture, salmon management policies, and research approaches. There was much to learn, absorb, and follow.

With Kine Kjær's participation, there was also a focus on learning about Mi'kmaq art. The delegation met with Indigenous artist Alan Sylliboy in his studio, learning about the mythology and culture underpinning his artwork. Kjær later developed the project logo and approach to art based on the Unama'kivisit.

Alan Syliboys art studio. Photos by Kia Krarup Hansen & Camilla Brattland

Pjila’si - Welcome

The first day we all gathered at Dalhousie University in Halifax, meeting some of the staff who work on Indigenous issues at the university. We were graciously and warmly welcomed to their home with wonderful introductions by Mi’kmaw Elder Ann LaBillois and John R. Sylliboy, vice-provost of Indigenous Relations at Dalhousie. Through storytelling, they both shared perspectives on nature and our common responsibility in interactions with our surroundings, and some of the shared challenges that Indigenous Communities face.

«The state has been dismantling our knowledge system, when closing the area for access, like now due to environmental conditions. » John R. Sylliboy

People, Land and Waters - Differences and Similarities

«There were so many similarities between what I was born and raised with, and what you saw and heard about over there» Elisabet Erke

Through shared explorations and discussions on each other’s cultural traditions and practices, shared values and perspectives of the Mi’kmaw and the Sámi soon became apparent. For example, during a cultural Journeys on Goat Island (Eskasoni) the Mi’kmaw traditional dwellings, tools, stories, songs, and dances, were demonstrated to us and showed many similarities to Sámi artifacts and traditions.

Goat Island. Photo by Kia Krarup Hansen.

«Otherwise, the Mi’kmaw share a common mindset, a closeness to nature and harvesting from nature. They are grateful to the nature they are a part of, and ask permission to take part in the river, or the forest if they are going to gather herbs and berries. These are old traditions also in the Sámi, and some of this is making a comeback.» Elisabet Erke

Both people share a close connection to the natural surroundings through practices of harvesting, storytelling, rituals and the spiritual. The Indigenous communities have their own cultural institutions for the stewardship of their land and waters, embedded in their own world-views: like asking for permission to harvest, sharing resources, storytelling traditions, and other ritual practices and places which underline values of importance. TheKluskap Cave is an important sacred place for the Mi’kmaq people. They consider the Cave the center of the universe and the final resting place of Kluskap. See Kluskap’s Sacred Cave | Mi'kmawey Debert Cultural Centre.

Kluskap Cave. Photo by Kia Krarup Hansen.

Blocked access to land and waters

Perhaps the most striking aspect of arriving in Unama’ki to the Sámi participants, was the differences in terms of landscape and climate. Where the Deatnu-Tana river in Sápmi is covered in ice during winter, it has been decades since the Bras d’Or lakes was covered in ice. However, there were also similarities when it comes to governance challenges both peoples face. Canadian authorities have introduced restrictions on the use of and access to resources in Unama’ki. Due to the warm and dry weather that had lasted for months, a ban on entering forests and lighting fires had been established. People could risk a fine for just being in the forest. As visitors, the Sámi delegation found this similar to the salmon fishing ban to the Deatnu – Tana river, which has now been banned for five years in a row. The young salmon ambassador Camilla Mudenia expressed that it was frightening to see how the Canadian state could close off whole areas that were significant to the Mi’kmaw.

Locals pointed out how the ban limits their rights to culture and sustaining themselves, as they are not allowed to go into the forest to harvest food, to gather medicinal plants, or how it limits cultural, spiritual practices like smudging.

Closed Land. Photos by Kia Krarup Hansen

Inspirations

The implementation of Indigenous values through local self-determined management of natural resources was inspiring. Here, the concept of Netukumlink is important, which to the Mi'kmaw means the use of the natural bounty provided by the Creator for the self-support and well-being. This carries similarities to the Sámi concept of birgejupmi which means being able to sustain oneself from the land. This was one of the many striking commonalities in the meeting between the Mi'kmaw and Sámi Indigenous cultures. As visitors, we also found the implementation of concepts and ways of thinking of multiple society levels, such as the medicine wheel and “Two-Eyed Seeing”, inspiring, and something to reach for back home. Another example is the way UINR collaborates on river restoration with government partners.

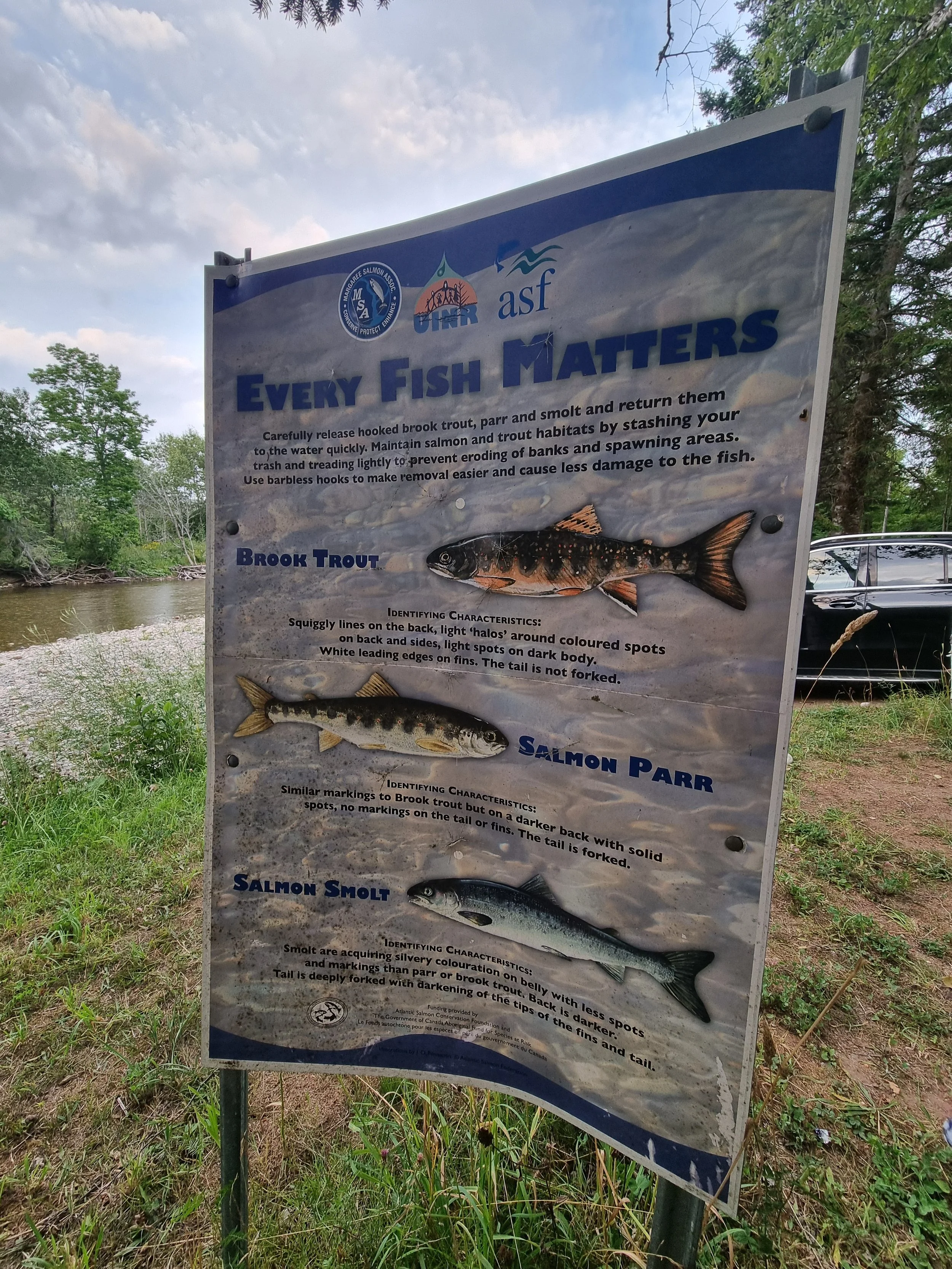

Signs on river restoration. Photos by Camilla Brattland.

Similar cultural concepts guiding the management of natural surroundings and community are present in Sámi tradition and language as well (e.g. meahcci, meahccesteapmi which are concepts similar to wilderness and caring for nature or the wilderness), and we discussed amongst us how the implementation of these concepts in the public language of resource management could be done more explicitly to show the value of Sámi culture in management of land and water resources. We also noticed how the Mi’kmaw seemed to be more open about their spirituality and rituals connected to nature and to salmon fishing. In Sápmi, this often belongs to a more private sphere.

The Margeree River. Photo by Kia Krarup Hansen

Shared Pasts and Challenges

The Sámi delegation noticed how the Mi'kmaq people and the Sámi people share a difficult history of assimilation and colonization by the states. Boarding schools have been used in the context of colonization in both Canada and Norway. Colonization by Western authorities has been a significant part of the history of both groups. As Western societies have come to dominate both Mi’kmaw and Sámi, both experience conflict with the States on different attitudes and practices of how to interact with nature. The commonalities between the two Indigenous groups therefore begins there shared challenges related to assimilation and colonization.

The Canadian State and its Relationships to its Indigenous people

The Canadian State governance differ from todays Norwegian State governance in Sápmi, which is an obstacle to achieving self-determination. In Canada, Indigenous peoples have self-governed areas, and as visitors, we noticed the clear Canadian and Indigenous laws that allows for local management. This has allowed for the successful incorporation of cultural, moral principles of moderation and taking only what is needed into local laws of self-governance.

Through a principled approach, Indigenous peoples in Canada have managed to resolve many past conflicts with the authorities. Reserves can be small or large, but are always characterized by self-governance, and have created areas to enter into negotiations with the authorities. However, and despite treaties with the British Crown that are still in full force and effect, jurisdiction is limited to reserves and co-governance is not yet realized.

The Mi’kmaw have also built indigenous organisations, like CEPI (The Bras d'Or Lakes Collaborative Environmental Planning Initiative) and UINR (Unama’ki Institue of Natural Resources), which were an inspiration for the visiting delegation.

During a full conference day at the Membertou Conference Centre, the CEPI as well as the Bras d’Or Lakes Biosphere Reserve shared their work on partnerships and co-governance. Representatives from UINR and Eskasoni Fish and Wildlife Commission shared their projects on stewardship and climate change response, including the formation of an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA). The IPCA was presented as an example of Mi’kmaw-led nature governance initiatives, with Mi’kmaw values and principles at the heart of the organisations.

In some of the rivers in Unama’ki where salmon fishing is possible, only "catch and release" is allowed for tourist and recreational fishing, while Indigenous peoples with fishing rights can choose to fish for salmon for food in a few rivers. In many cases, they choose not to exercise this right because they see that salmon stocks are so low.

“The state had confidence that the indigenous people, the Mi'kmaq people, did not take more than they needed.», Elisabeth Erke

However, for the Mi’kmaw, a long history of legal battles lies behind achieving such self-determination. One of the key cases occurred in the 1990s when Mi’kmaw fisher Donald Marshall Jr. was fined for fishing eels. Based on the subsequent court case, in addition to other cases, Indigenous peoples have affirmed right to fish for food and for social and spiritual purposes, even if the species is endangered, albeit very limited. The court case is well known and the story told in multiple ways, such as at the Membertou Cultural Centre where the exhibition showcases the eel trap that was confiscated by the government.

Eel trap confiscated from Donald Marshall jr. Showcased at the Membertou Cultural Centre. Photo by Tommy Ose.

Camilla Mudenia, young Sámi from the Deatnu – Tana river valley, noticed the many good examples of solutions and cooperation on regulation of salmon harvest. That the Mi’kmaw were able to participate in fish countings (swim thrus) and adjust the quotas after agreed-upon numbers was one of these.

Different Approaches and Attitudes from the State

This is different to the current situation in Norway, e.g. with regards to the Norwegian supreme court’s recent decision in Fosen wind power-plant case in the South-Sámi area. The Canadian government took the decisions in key court-cases that they lost seriously, and as a consequence, they developed new policies for management of local resources for First Nations. Such initiatives can increase respect, trust and platforms for further cooperation.

Shared values and attitudes towards collaborative management of resources are recognized by the authorities to a much greater extent than in the Deatnu - Tana River system, where locals are frustrated about the lack of power through participation in decision making processes with state entities that regulate the fishing, even though local Sámi-led administrative institutions exist. The decision to build a salmon trap across Deatnu in the summer of 2025, being but one such example.

«Canada is a federal state that has initially given a lot of self-determination to both territories and provinces, municipalities and counties», Sámi parliament councillor Elisabeth Erke points out. «Norway, on the other hand, is a centrally controlled nation», and Elisabeth believes the country bears the hallmarks of that, not least when it comes to the relationship with the Sámi.

At The Margaree River Fish Hatchery

One of the main stops was the Margaree River, which is fished by the Mi’kmaw, and the provincially-managed Margaree River Fish Hatchery. The mass production of fish in the artificial environments of the hatchery, provides fish to cover for losses associated with “catch and release” sports-fishing, which has a long history in the region.

Margeree River Fish Hatchery. Photo by Tommy Ose

During the tour at the hatchery, one of the visiting salmon ambassadors from Deatnu, Jon Christer Mudenia, commented on how the practice of catch and release goes completely against Sámi culture. For the Sámi, salmon fishing is not done as a recreational activity, but is part of birgejupmi, a way of life where knowledge and practice meet when making sure you have what you need, harvesting and living in harmony with your surroundings over time.

Looking at the current situation in the Deatnu river-system, it can be described as a “double-bind”, as a large part of the local economy is connected to fish-tourism, as well as the cultural tradition, is connected to salmon fishing.

Spearfishing with the Sylvester Brothers

Spearfishing. Photo by Kia Krarup Hansen.

One of the local traditional methods for fishing salmon is spearfishing. We were given a thorough presentation of how this is done in practice by the Sylvester Brothers, Darren and Joey. "Spearing" involves going into the river with a salmon spear and spearing the fish at night (though the demonstration was given to us at day light). Limited fishing with traditional methods aims to maintain culture, values, and relationships with salmon. We took part in the ritual of offering tobacco to the river before the fishers entered it.

Sharing the salmon which is caught is a very important cultural practice, particularly with elders and those who are not able to go fishing anymore. As guests, we also received salmon from the Sylvester brothers for one of our dinners in Eskasoni. Sharing the catch is also present in Sámi culture. For the Sámi delegation, the multiple similarities in e.g. world views, hunting techniques and spirituality and more were striking and the source of further discussions into the evening as stories were exchanged.

“Two-Eyed Seeing” - Meeting Albert Marshall

On the last day of the trip, we had a group discussion and meeting with Elder Albert Marshall, a well-known Elder, scholar, and philosopher, who is the one behind the concept of 'Two-Eyed Seeing,' one of the key principles of the Sharing our knowledge project.

Group meeting with Elder Albert Marshall and Sámi Parliament Councillor Elisabeth Erke gifting Marshall. Photos by n.n. and Kia Krarup Hansen

It was a memorable experience to meet Marshall and discuss his thoughts on both global issues and specific local conditions, both from a research and philosophical perspective. The Sámi delegation gifted him the book “River Sámi” published by the project partner DeanuInstituhtta, on the occasion of the 2nd International Indigenous Salmon Peoples Gathering in Karasjok, Norway, October 2024.

Albert shared some key principles with us:

1) Staying connected to nature

2) Consider the consequences of your individual actions, and

reflect on how you personally can improve in this context

3) Care for water, as no being can survive without it

4) Use scientific knowledge towards positive change

5) Speak up against injustice

Weaving of Knowledge Systems

Albert reminded us of how scientific knowledge has also been used to destroy nature, and it is important that we work to change this, and now use scientific knowledge for positive change.

“You take todays and yesterday’s teachings together”, Albert Marshall

During our stay in Unama’ki we had the opportunity to, join weaving of sweetgrass demonstrated by a Mi’kmaw couple at the Membertou reserve meeting.

Sweetgrass braiding. Photos by Kia Krarup Hansen.

Weaving is a metaphor for how traditional knowledge and western scientific knowledge can be combined. Aquaculture industry has brought much scientific knowledge, and we should use that knowledge and techniques to improve and overcome environmental challenges. In this way, the industry offers also “a helping hand, not just extract”.

The delegation, consisting of people from various institutions, allowed for different impressions and discussions within the group, bringing diverse perspectives and voices. This way, it is not just a project among researchers, but includes different layers of society, which we found very valuable. As visitors in Unama’ki, we thoroughly enjoyed ourselves and found the trip very rewarding.

Ollu Giitu / thank you in Mi’kmaq - Welali’oq