River Dialogues Across Sápmi

Written by Emalie Hayes, Alitta Sylliboy Patles, and Camilla Brattland

Our River Dialogues began under the midnight sun of Tromsø/Romsa, and then continued through Olmmáivággi/Manndalen, Álta/Alta, crossing into Kárášjohka/Karasjok, and culminated in two‑day symposium on the banks of the Deatnu/Tana River in Ohcejohka/Utsjoki, Finland. Supported by the SUN project (led by Linneaus University, Sweden) and the Sharing Our Knowledge project (UiT, Norway), we wove together site visits, exhibitions, traditional and new salmon‑trap demonstrations, and panel discussions.

Tromsø/Romsa: Midnight Sun & UiT Welcome

We arrived in Tromsø/Romsa in a period of 24‑hour daylight (Figure 1) and were welcomed at Árdna, the Sámi house on UiT’s Arctic University of Norway campus (Figure 2). The Árdna is a Sámi cultural center with symbolic value, constructed using materials from Sámi-populated areas and crafted by Sámi artisans. In the Árdna, we introduced ourselves and the projects or independent research we represent, while expressing the hardships that Indigenous people face in their relationship with the earth, river, and salmon, and what we can do to make a change for the future - paving the way for the River Dialogues Across Sápmi. In Tromsø, we met with others who joined us in the River Dialogues Across Sápmi workshop. Those of us on the Sharing Our Knowledge team include Camilla Brattland, who also served as the trip coordinator, Heather Smith, and Andrea Momblanch from Cranfield University. From Dalhousie University, Alitta Sylliboy Patles, a Mi’kmaq woman who also works at the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources and a graduate student, Madison Gouthro, a PhD student, and Emalie Hayes, a postdoctoral researcher, joined the trip. Another group that joined us was the “Surviving the Unthinkable” (SUN) research group, led by Gunlog Für, Janne Lahti, and Lindsay Doran. Zena Cumpston of the Barkandji Nation and Maddison Miller of the Dharug Nation joined the trip as independent researchers from Australia. Later, we met with Katri Somby, a Sámi historian and a local Indigenous person from the Deatnu River.

Olmmáivággi/Manndalen: Centre for Northern Peoples

Figure 3 Market in Skibotn

On the road to the Centre for Northern Peoples in Olmmáivággi/Manndalen, we stopped at the Market in Skibotn (the driest place in Norway) to explore its historic trade market. The region’s land still incorporates drying racks for fish, a nod to how dried codfish once fueled Sámi trade and even supplied Swedish troops during one of the historic Nordic wars. Language emerged as a cornerstone of identity: owning land here means belonging to fjords and mountains as much as to each other.

We also stop along the way at Nordkjosbotn Rasteplass to take in the views of the Fjords!

Back row left to right: Alitta Sylliboy Patles & Madison Gouthro. Front row left to right: Andrea Momblanch, Emalie Hayes, & Heather Smith

Left to right: Alitta Sylliboy Patles, Madison Gouthro, Gunlog Für, Emalie Hayes, & Heather Smith

Visiting the exhibition “Så når ikke øyet lenger” (“then they eye reaches no further”) at the Centre for Northern Peoples offered an introduction to Sámi history and culture (Figure 6). The exhibition is organized around four central themes; belief, duodji (handicraft), language, and living conditions, which together present a worldview of Sámi life, both past and present. Rather than focusing on chronology, the exhibit uses cultural and everyday objects to explore how traditions have been maintained, adapted, and reintroduced through projects like Bååstede, which returned Sámi objects to local communities. Cultural objects (some of unclear origin) revealed knowledge that transcends text. As curator and museum director Lisa Vangen reminded us, “although these items are silent, they continue to speak through the traditions which they represent”.

The Centre for Northern Peoples in Olmmáivággi/Manndalen

Hung above the stairs of the “Så når ikke øyet lenger” exhibition is a vandalized road sign from Kåfjord municipality from the 1990s when bilingual road signs featuring both Sámi and Norwegian languages were introduced in Northern Norway (Figure 7). It bears both paint splatters and bullet holes deliberately aimed at obscuring the Sámi place‑name. A stark, tangible reminder of the period’s violent attempts to erase Sámi language and identity. The yarn‐spinning wheel on the sign is the charge from Kåfjord municipality’s coat of arms. It was chosen to honour the area’s longstanding tradition of home‐based handicrafts, which was historically a women’s household activity, making it unique in centering a “female” emblem.

Road sign with Sámi name for the Gáivuotna/Kåfjord kommune/municipality painted over, as the Centre for Northern Peoples

After a lunch of reindeer stew, we walked from the exhibition centre down closer to the river where we gathered in a large wooden building, a Nisga’a Longhouse which is part of the Centre’s collection of northern Indigenous peoples’ buildings. Inside we saw Sámi art line the walls, and vibrant textiles lined the floors (Figure 8).

Henrik Olsen from the Riddu Riđđu Festivála presenting the festival in the Nisga’a Longhouse

Inside the longhouse, we gathered in a circle to continue our river dialogues. Here, we saw the film “The Dream About the River” by Ingeborg Solvang and heard how the nearby rivers once teemed with salmon so thick you couldn’t see the bottom of the waters. We also learned about the Riddu Riđđu Festivàla, which means “little storm on the coast” in Sámi language. This event has been held each July in the coastal community of Gáivuotna/Kåfjord for 28 years. Originally focused on reinforcing pride in Sámi culture, it gained national recognition in 2009 as one of Norway’s premier cultural gatherings. Today, it stands as one of Europe’s foremost international Indigenous festivals, showcasing Sámi and global Indigenous creativity through a rich lineup of music, film, seminars, workshops, visual arts, literature, and theater for audiences of all ages. During our discussions, we heard the story of a woman who stood on the riverbank with an empty basket, waiting patiently for the salmon’s return. It reminds us of the deep connection the Sámi community maintains with their rivers, patiently awaiting the salmon’s revival.

Alta, Norway: Rock Carvings & World Heritage Rock Art Centre

At the World Heritage Rock Art Centre, carvings dating back 7000 years illustrated the deep connection between Sámi hunters, fishers, and the landscape. The rock carvings were made by Sámi people who lived off hunting and fishing. They reflect not only the animals and the environment they relied on, such as reindeer, elk, bears, dogs, foxes, hares, birds, halibut, salmon, and whales, but also their beliefs and rituals. Many of the figures are thought to represent elements of stories or myths, and the scenes show everything from hunting and gathering to dancing and ritual practices. We learned that the age of each panel is read by its height above sea level, a testament to post‑glacial change. Interestingly, in the earlier carvings (Figure 9) you can see how the carvings display antlered animals (possibly reindeer), alongside hunters and possibly their equipment (e.g., net-like grids for fishing, bows for hunting).

Rock carvings in Alta

As we walk along the rock carvings path, we moved through time and could see the shift in how the land, boats, tools and wildlife shifted by the carvings (Figure 10): simpler reindeer, abundant birds, and elaborately carved boats crowned with moose heads. At the end of the tour, the tour guide left us with a powerful reflection:

“While earlier generations left behind carvings, stories, and deep connections to the land, future generations will inherit traces of the present in the form of plastic, metal, and waste.”

During our visit to the World Heritage Rock Art Centre our guide also described the ongoing issues over how the carvings were painted initially with standard house paint, and how this has been found to damage the rocks. Therefore, the Rock Art Centre has ongoing plans to restore the carvings to their original state.

Rock carvings in Alta

Later, Sámi historian Katri Somby recounted the 1970s hunger strikes to defend reindeer‑hunting rights and halt the Alta River dam, an event that reshaped both Norwegian hydro‑policy and Sámi rights policies. Seven days without food during this hunger strike underscored this idea of how knowledge shared is power multiplied. The Sámi individuals willing to risk their lives for their river rights exemplifies the profound cultural, legal, and spiritual bonds they share with these waterways. The presentation by Katri underscored that acknowledging river rights is inseparable from affirming Indigenous sovereignty. Lastly, when departing our visit at the World Heritage Rock Art Centre, we were left with the following thought of how:

“Only when you share knowledge, can you make individuals care about something and only then will a person begin to develop a sense of belonging and responsibility to care for their lands.”

Kárášjohka/Karasjok, Norway

In Kárášjohka/Karasjok, we were given a personal tour of the Sámi Parliament of Norway by Sámi historian Katri Somby, who guided us through the building’s architecture and legislative chambers. Her insights on how Indigenous representation influences governance enriched our perspective on legal frameworks for river rights in the north. Stepping into Vandrehallen, the Parliament’s larch‑clad foyer, we were greeted by large windows framing the surrounding forests and grand wooden corridors. Walking by the library, which is home to 30,000 volumes across nine Sámi languages, plus specialist works in English, and Latin. As you enter the plenary assembly hall, at the very heart of the Sámi Parliament, your attention is drawn to the large artwork by Hilde Schanke Pedersen (Figure 11).

Madison Gouthro, Emalie Hayes, & Alitta Sylliboy Patles at the Sámi Parliament building in Karasjok

Cast in concrete with abstract forms, its cobalt backdrop and gilded accents conjure the region’s light and landscapes. The space itself is a semi‑circular, peaked chamber, with high windows for light. The lavvu (the Sámi cone-shaped mobile tent, resembling a tipi) shape of the plenary assembly hall was apparently inspired by the way in which the people of the north place wood out to dry in piles after felling and trimming it.

The Sámi Parliament covers seven electoral districts and sends 39 delegates to represent both Sámi‑specific and national parties. Currently, about 14,000 persons are on the Sámi electoral roll. Decades of forced Norwegianization discouraged many from registering, but the numbers are now steadily growing.

Ohcejohka/Utsjoki, Finland

Before crossing into Finland, we visited the pink salmon trap close to the Deatnu/Tana river mouth, organized in collaboration with the Norwegian Veterinary Institute, Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, and local scientists. The purpose of the visit was to learn more about ongoing efforts to monitor and manage both pink salmon (an invasive species) and the Atlantic salmon to the rivers. Pink salmon, originally from the Pacific, have increasingly established themselves in Norwegian rivers and pose potential threats to the Atlantic salmon. The salmon traps are designed to intercept migrating salmon using metal grates spaced ~3 cm apart (Figure 12), wide enough to allow native Atlantic salmon and sea trout to pass through, while pink salmon are retained. This selective design is intended to reduce the need for manual sorting, though some handling may still be involved. This method, while considered an important management tool by biologists, comes with its controversy. Criticism and concerns have been raised about the stress and potential harm caused by physical handling, especially when sorting is required.

Cages as part of the salmon trap in Deatnu/Tana

In a workshop at the Wild Salmon Centre in the town of Tana bru, we team‑mapped our home watershed of Unama’ki/Cape Breton (Figure 13). Local participants mapped the Varanger fjord and the Deatnu/Tana river. Combining Western and Mi’kmaq knowledge, we traced what we believed to be the greatest climate impacts on fish runs, water quality, and cultural ceremonies to the rivers in our homes. This exercise was conducted by our Cranfield University colleagues in the broader efforts to co‑produce flood maps and Hazard Mitigation Plans, blending traditional and technical know‑how to secure funding and protect rivers.

Mapping impacts of climate change on rivers

In Ohcejohka/Utsjoki, we took part in the River Dialogues, a discussion series that brought together scholars, doctors and community voices to explore the role of rivers in connecting knowledge across disciplines along the Tana River (Figure 14).

One of the Tana river tributaries, the Utsjoki river

In the first session, Sharing Knowledges Across Borders and Disciplines, we heard from Professor Harald Gaski who spoke about the academic challenges of applying the concept of Two-Eyed Seeing. Dr. Gaski emphasized that in many scientific settings, many still believe that there can only be one truth, which limits space for multiple ways of knowing. He presented that while North America has made some meaningful progress in incorporating Two-Eyed Seeing into academic and scientific frameworks, a key gap is that Indigenous people are often excluded from the interpretation and analysis stages of Indigenous-focused research. As a result, Western scholars may misinterpret or misrepresent core outcomes that cannot be fully translated across worldviews or languages.

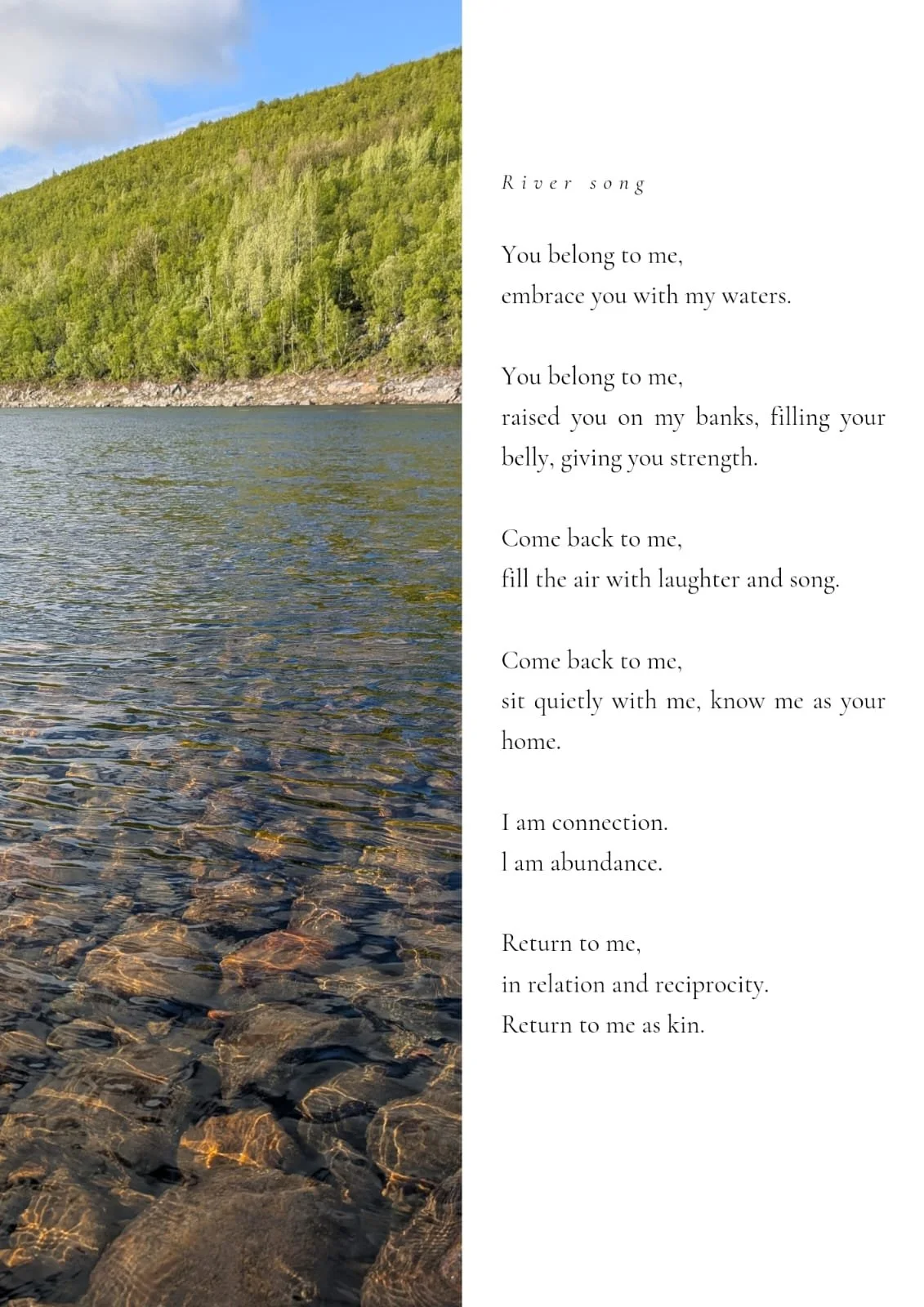

In the second session, we heard from Professor Gunlög Fur and postdoctoral researcher Lindsay Doran from the University of Eastern Finland. They spoke about how natural sciences, while important for identifying what is happening in the context of climate and ecological change, often fall short in explaining the how and why. It’s through the human sciences, which draw on cultural, historical, and social perspectives, that we begin to understand the deeper context behind these changes. Another powerful idea they shared was the importance of the cultural legacies left by ancestors. If those before us hadn’t preserved their knowledge through carvings, art, and other tools, much of that understanding would have been lost. These forms don’t exist for us to replicate today, but to learn from, through offering guidance, perspective, and context for how we carry this knowledge forward. Aboriginal Darug woman Maddison Miller closed the River Dialogues with a powerful sharing of thoughts and stories from the week, creating a beautiful narrative from the session (Figure 16).

Figure 16 Poem written by Maddison Miller

Concluding Thoughts

Our week across Sápmi showed that rivers are more than channels of water, they are living records of culture, history, and law. Each watershed we visited bears stories of fish runs so abundant the riverbed vanished beneath their scales, and of communities whose identities and rights are inseparable from those flows. When we lose a river, we lose language, ceremony, and a sense of belonging. Today, climate change is squeezing these systems from both ends. Extreme floods and prolonged droughts disrupt spawning cycles; hydroelectric projects and invasive species reshape habitats; and legal frameworks too often ignore Indigenous voices. If we want rivers to endure, we must embed Sámi stewardship and other Indigenous knowledge at every decision point.

“When multiple worldviews guide river management, we not only protect ecosystems, but we also honor the communities who have cared for them for millennia.”